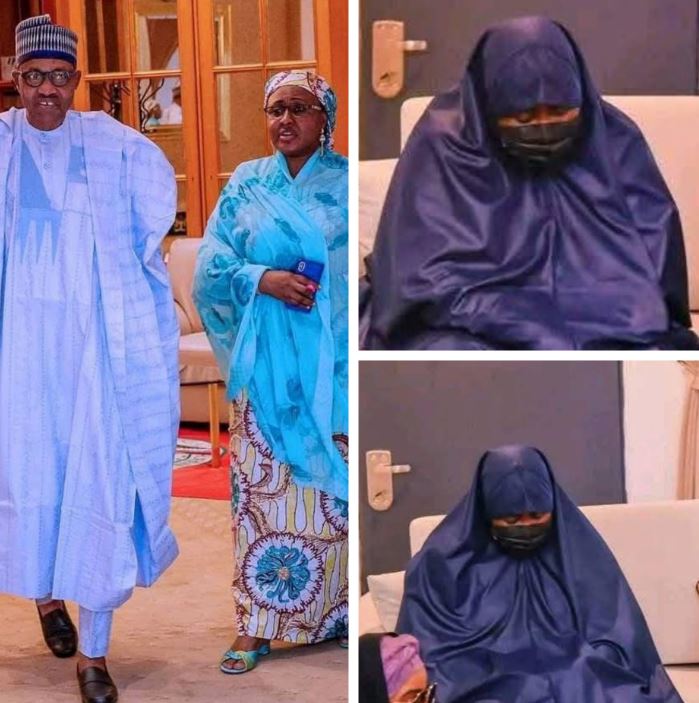

When news emerged that some of the Chibok schoolgirls, abducted by Boko Haram in 2014, had declined to return home with the batch of 82 freed in May, the world found it difficult to believe.

Not even the release of a Boko Haram video showing some hijab-clad, Kalashnikov-wielding girls saying they were happy in their new lives, was enough to convince people. “They must have been coerced,” some said.

“It must be Stockholm syndrome,” others said. What else could explain why any girl, any woman, would choose to remain with such horrible men?

Yet, some women rescued by the Nigerian military from captivity are willingly returning to Boko Haram’s Sambisa forest hideout in north-eastern Nigeria to be with these same horrible men.

‘Fairytale life’

In January, I met Aisha Yerima, 25, who was kidnapped by Boko Haram more than four years ago. While in captivity, she got married to a commander who showered her with romance, expensive gifts and Arabic love songs.

The fairytale life in the Sambisa forest she described to me was suddenly cut short by the appearance of the Nigerian military in early 2016, at a time her husband had gone off to battle with other commanders.

When I first interviewed Aisha, she had been in government custody for about eight months, and completed a de-radicalisation programme run by psychologist Fatima Akilu, the executive director of the Neem Foundation and founder of the Nigerian government’s de-radicalisation programme.

“I now see that all the things Boko Haram told us were lies,” Aisha said. “Now, when I listen to them on the radio, I laugh.”

The pull of power?

But, in May, less than five months after being released into the care of her family in north-eastern Maiduguri city, she returned to the forest hideout of Boko Haram.

Over the past five years, Dr Akilu has worked with former Boko Haram members – including some commanders, their wives and children – and with hundreds of women who were rescued from captivity.

“How women were treated when in Boko Haram captivity depends on which camp a woman was exposed to. It depends on the commander running the camp,” she said.

“Those who were treated better were the ones who willingly married Boko Haram members or who joined the group voluntarily and that’s not the majority. Most women did not have the same treatment.”

Aisha had boasted to me about the number of slaves she had while in the Sambisa forest, the respect she received from other Boko Haram commanders, and the strong influence she had over her husband. She even accompanied him to battle once.

“These were women who for the most part had never worked, had no power, no voice in the communities, and all of a sudden they were in charge of between 30 to 100 women who were now completely under their control and at their beck and call,” Dr Akilu said.

“It is difficult to know what to replace it with when you return to society because most of the women are returning to societies where they are not going to be able to wield that kind of power.”

Still in shock

Apart from loss of power, other reasons Dr Akilu believes could lead women to willingly return to Boko Haram include stigmatisation from a community which treats them like pariahs because of their association with the militants, and tough economic conditions.

De-radicalisation is just one part of it. Reintegration is also a part of it. Some of them have no livelihood support built around them,” Dr Akilu said.

“The kind of support you have in de-radicalisation programmes does not follow you when you leave. They often come out successful from de-radicalisation programmes but they struggle in the community and it is that struggle that often leads them to go back,” she said.

Recently, I visited Aisha’s family, who were still in shock at her departure and worried about her wellbeing.

Her mother, Ashe, recalled at least seven former Boko Haram “wives” she knew, all friends of her daughter, who had returned to the Sambisa forest long before her daughter did.

“Each time one of them disappeared, her family came to our house to ask Aisha if she had heard from their daughter,” she said. “That’s how I knew.”

Some of the women kept in touch with Aisha after they returned to Boko Haram. Her younger sister, Bintu, was present during at least two phone calls.

“They told her to come and join them but she refused,” Bintu said. “She told them she didn’t want to go back.”

Life on track?

Unlike some former Boko Haram “wives” I’ve met, who are either struggling to survive harsh economic conditions or dealing with stigma, Aisha’s life seemed to be on track.

She was earning money from buying and selling fabric, regularly attending social events and posting photos of herself all primped up on social media, and had a string of suitors.

“At least five different men wanted to marry her,” her mother said, pointing out that there could be no greater form of acceptance shown to a woman, and presenting this as evidence that her daughter faced no stigma whatsoever from the community.

“One of the men lives in Lagos. She was thinking of marrying him,” she said.

But, everything went awry when Aisha received yet another phone call from the women who had returned to the forest, informing her that her Boko Haram “husband” was now with a woman who had been her rival.

From that day, the vivacious and gregarious Aisha became a recluse.

“She stopped going out or talking or eating,” Bintu said. “She was always sad.”

Two weeks later, she left home and did not return. Some of her clothes were missing. Her phones were switched off. She took the two-year-old son fathered by the commander in the Sambisa forest, but left the older one she had with the husband she divorced before her abduction.

“De-radicalisation is complicated by the fact that we have an active, ongoing insurgency. In cases where a group has reached settlement with the government and laid down their arms, it is easier,” Dr Akilu said. “But, when you have fathers, husbands, sons still in the movement, they want to be reunited, especially women.”

Asta, another former Boko Haram “wife”, told me that she has heard of the many women returning to the group, but has no plans to do so herself.

However, the 19-year-old described how terribly she misses her husband, and how keen she is to hear from him and to be reunited with him.

She insisted that she would not return to the forest, not even if he were to ask her.

“I will tell him to come and stay here with us and live a normal life,” she said.

But as with Aisha, the desire to be with the man she yearns for may turn out to be more compelling for Asta than the aversion to a group responsible for the deaths of thousands of people in north-east Nigeria, and for the displacement of millions who are struggling to survive in refugee camps.